The environmental strategy and the programme (Environment and Planning Act blog series)

The Environment and Planning Act introduces two new policy instruments: the environmental strategy (as successor to the national policy vision) and the programme. In this blog post, we take a closer look at the nature and function of both instruments within the new environmental law system.

This post is part of the Environment and Planning Act blog series. In the run-up to the Environment and Planning Act (the Act) that will enter into force on 1 January 2024, we each time highlight a specific topic of this law in this blog series.

In the environmental strategy and the programme, administrative bodies may include policy goals for the quality of the physical living environment and detail how they will be achieved. An administrative body thereby gives policy substance to its duties and powers and thus to the government's care for the physical living environment (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 114). Before zooming in on the environmental strategy and the programme, we will first provide a brief overview of the various types of instruments under the Act and the correlation between them.

Correlation between various types of instruments under the Act

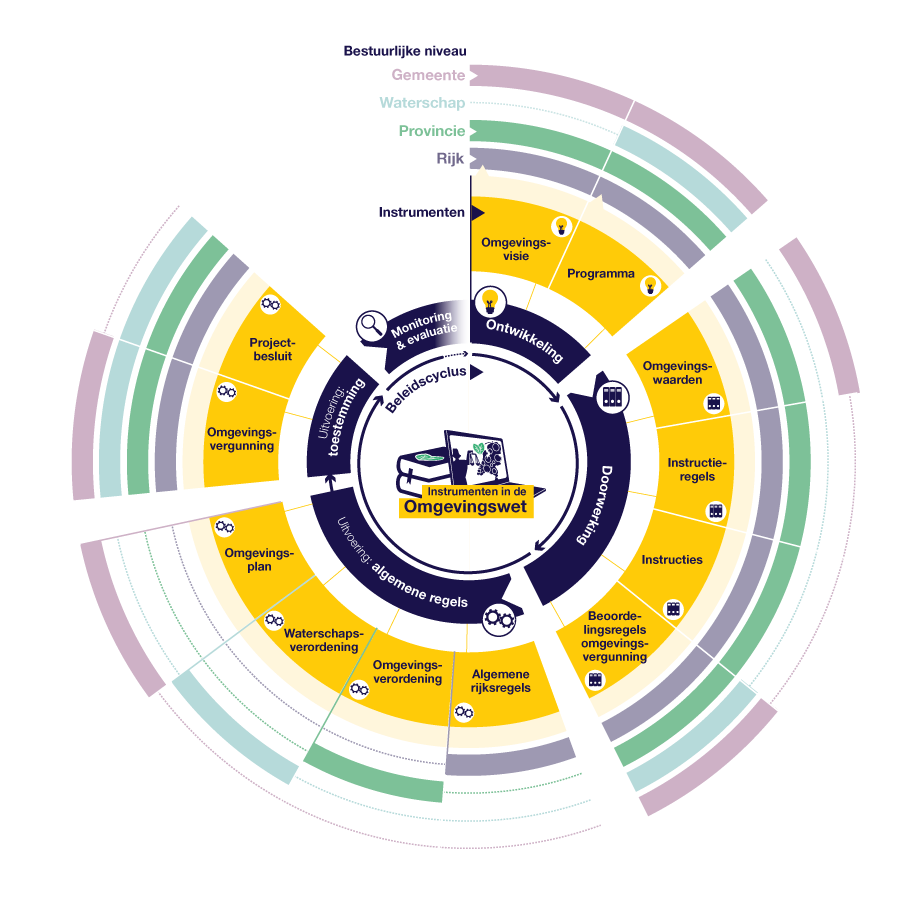

The instruments of the Act are divided into four types: policy development, policy implementation, general rules, and consent.

The environmental strategy and programme are instruments for policy development. These instruments are self-binding only. Policy is carried through to the decentralized level in the form of environmental values, instruction rules, instructions and assessment rules for environmental permits. The general rules of the national and decentralised governments are set out in the environmental plan, the water board bylaw and the general rules it contains, the Environment and Planning Decree and the rules it contains, and the general government regulations. These instruments steer activities in the right direction where possible and provide clarity on what is and is not permitted in the physical environment. Finally, for cases that do not fit within the applicable rules, the Act provides for the possibility of giving permission for such cases in the form of an environmental permit or project decision (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 8).

While the various instruments (and types of instruments) are easily distinguishable from each other in a theoretical sense, they continuously overlap in practice. This is illustrated below on the basis of environmental values. Environmental values are measures of the desired condition or quality of the physical living environment (or a specific part of that environment), or the permissible burden from activities or permissible concentration or deposition of substances in the physical living environment (or a specific part of that environment). Environmental values are expressed in measurable or calculable units or otherwise in objective terms (Article 2.9 of the Act) and are primarily directed at the government (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 50). In principle, environmental values can therefore be characterised as instruments for policy implementation, since they determine the policy to be implemented. But, in addition, environmental values are also closely related to other instruments and types of instruments:

- The instruments of the type of general rules, such as the environmental plan (Article 2.11 of the Act) or the environmental regulation (or the general rules it contains) (Article 2.12 of the Act) can be used to establish environmental values.

- By means of instruction rules (the instrument belonging to the type of policy effect), the national government can ensure that an environmental value is carried through to local rules.

- Assessment rules for the application for an environmental permit (as part of the consent instruments) may provide that this permit will be granted only if certain environmental values are observed (see, for example, Article 8.17(1) of the Living Environment Quality Decree).

- In the context of policy development, a programme requirement applies if an environmental value is exceeded or is about to be exceeded (Article 3.10 of the Act).

Environmental strategy

In the Act, the structuurvisie (national policy strategy – Article 2.1(1) of the Wet ruimtelijke ordening (Spatial Planning Act)) has been replaced by the omgevingsvisie (environmental strategy). The environmental strategy and the national policy strategy are similar, but there are nevertheless a number of important differences: (i) in the environmental strategy, several sectoral visions are combined into a single integrated strategy (Article 3.1 of the Act); (ii) early public participation plays an important role (Article 10.7(1) of the Environment and Planning Decree; and (iii) unlike in the national policy strategy, the inclusion of an implementation paragraph is no longer mandatory in the environmental strategy (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 118).

Environmental strategy

An environmental strategy is a coherent strategic plan for the physical environment. The environmental strategy contains one integral long-term vision of an administrative body on the necessary and desired development of the physical living environment in its administrative boundary (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 51).

No content requirements or formal requirements apply to the environmental strategy. Administrative bodies are therefore given room to organise the strategy as they see fit. The environmental strategy must, however, contain the following components (Article 3.2 of the Act):

- an outline of the quality of the physical environment;

- an outline of the proposed development, use, management, protection and preservation of the territory; and

- an outline of the integrated policy to be pursued for the physical environment.

According to the legislature, the environmental strategy may also include aspects other than those of the physical living environment, including non-area-specific topics, such as those currently included in an environmental policy plan (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 444).

The Act furthermore provides that the environmental strategy must take into account the environmental principles listed in Article 191 TFEU: the principle of precaution, the principle of preventive action, the principle that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source, and the ‘polluter pays’ principle (Article 3.3 of the Act). This legally ensures that these principles are taken into account at the start of the policy cycle already.

The inclusion of an implementation paragraph is therefore not a requirement but, if they so wish, administrative bodies may state in outline in the environmental strategy with which administrative bodies, in what manner and by means of which powers and instruments the policy will be implemented (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 119). Moreover, no updating obligation is included: administrative bodies are therefore offered optimal flexibility (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 120).

Adoption of environmental strategy

At both the municipal, provincial and state levels, each governing body adopts one environmental strategy (Article 3.1 of the Act). This ensures that a coherent strategy is established at the strategic level, rather than a sum of policy visions for various domains (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 114).

At the municipal level, the environmental strategy is drawn up by the municipal council, at the provincial level by the provincial council, and at the national level by the Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, in consultation with the ministers concerned (Article 3.1 of the Act). If they wish, administrative bodies may also adopt an environmental strategy for their territory jointly with other administrative bodies. In addition to an interprovincial or intermunicipal environmental strategy for provinces and municipalities (adjacent or other), a joint environmental strategy of, for example, a province and a municipality is also possible (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 443).

Water boards do not draw up an environmental vision, in view of its scope and integral nature (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 114).

The environmental strategy binds only the adopting administrative body itself. In light of this self-binding nature, no appeal is possible against the decision to adopt the environmental strategy. However, the enacting administrative bodies must ensure public participation and preparation in accordance with Article 3.4 of the Algemene wet bestuursrecht (General Administrative Law Act) (Article 16.26 of the Act). Anyone may submit opinions on the draft environmental strategy (Article 16.23 of the Act).

When adopting the environmental strategy, the administrative body must state how early public participation took place by explaining how citizens, companies, civil organisations and administrative bodies were involved in the preparation and what the results were (Article 10.7(1) of the Act). It must also state how the decentralised participation policy was implemented if the environmental strategy is adopted by the municipal or provincial council (Article 10.7(2) of the Act).

The creation of the environmental strategy may require an environmental impact assessment under Article 16.4.1 of the Act. Later in this blog series, we will discuss the participation obligation and environmental impact assessment under the Act in more detail.

Transitional law

Environmental strategies adopted before the Act enters into force will remain in force after its entry into force, provided that they meet the requirements of Article 3.2 and 3.3 of the Act (Article 4.10 of the Invoeringswet omgevingswet (Environment and Planning Act Implementation Act – the Implementation Act).

The obligation to adopt a municipal environmental strategy does not take effect immediately on the entry into force of the Act. The Royal Decree of 10 July 2023 (Stb. 2023, 267) provides that municipalities must have an environmental strategy in place that meets all the statutory requirements by 1 January 2027 at the latest. Until the municipality has an environmental strategy in place, the main points of the policy to be pursued from the environmental policy plan, the traffic and transport plan and the national policy strategy will continue to apply (Article 4.9(3) of the Implementation Act).

Environmental strategy issues

- Some national policy strategies are considered sector-wide programmes under the Act, such as the National Policy Strategy for Pipelines 2012-2035 (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 117).

- In order for policy development tools to function optimally, it is important that the environmental strategies and programmes remain current and aligned, so that they can continue to function properly.

- Especially compared with the national policy strategy, the environmental strategy is changing in character: from a sector-wide to an integral strategy. A successful environmental strategy therefore depends greatly on its implementation and requires a new way of policy-making.

Programme

The programme is a new instrument under the Act: before the Act, there was no general provision that authorised administrative bodies to adopt programmes. However, specific powers and obligations to adopt a programme did already exist, such as the obligation to adopt a national air quality programme (Article 5.12 of the Wet milieubeheer (Environmental Management Act)). The programme under the Act was addressed in an earlier Stibbe blog already (link).

Content of the programme

The programme is an instrument that elaborates the policy to be pursued in the area of the physical living environment (Article 3.5(a) of the Act). The program also sets out measures, which may be aimed at meeting one or more environmental values or at achieving one or more other objectives for the physical living environment (Article 3.5(b) of the Act). Although this does not expressly follow from the legislative text, we conclude that the legislature intended these requirements to be cumulative and that the programme must contain both policy intentions and measures (see e.g. Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 8: "the programme, a package of policy intentions and measures").

The programme is not an integral instrument. It follows from Article 3.5 of the Act that the policy and measures must relate to one or more components of the physical living environment. This means that the programme may have a sector-wide, area-based and/or theme-based character, and may include various aspects of the physical living environment (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 51). It may be considered remarkable that the programme is not an integral instrument, since the starting point is that decisions under the Act are integral as much as possible (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 31). The legislature has nevertheless not opted to do so, as each specific policy area has its own dynamics and characteristics, as a result of which integration may create a significant administrative burden (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 117).

The programme can be seen as a specific elaboration of the environmental strategy, although no legal link has been made between the environmental strategy and the programme (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 120).

Types of programmes

Various types of programmes can be distinguished under the Act.

- Mandatory programmes if an environmental value is or is about to be exceeded. If an environmental value is or is about to be exceeded, the government is obligated to draw up a programme to ensure compliance with the environmental value (Article 3.10 of the Act). If monitoring shows that the environmental value is being met again, it is possible to withdraw the programme (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 451).

- Mandatory programmes prescribed for the implementation of EU directives. These include existing plans and programmes that have bene (explicitly or implicitly) prescribed to implement EU directives (Articles 3.6 to 3.9 of the Act), such as the Noise Action Plan (Article 8 of the Environmental Noise Directive) and management plans for Natura 2000 areas (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 122).

- Non-mandatory or optional programmes. A programme may be set up under the Act on a party’s own initiative. Examples mentioned by the legislature are a municipal sewerage programme (Article 3.14 of the Act), a development programme (Article 3.14a of the Act) or a municipal bicycle action plan (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 122).

- Programmes with a programmatic approach. A programme with a programmatic approach is a special type of programme, regulated in Article 3.2.4 of the Act. It offers a specific way to meet environmental values or achieve other objectives for the physical environment, by managing the useable space in a given area and establishing measures. The programme also serves as a framework for assessing the permissibility of activities, meaning that the assessment may differ from the regular assessment rules (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 124). As a result, the programme with the programmatic approach has specific legal consequences, requiring compliance with a number of quality requirements elaborated in Article 3.2.4 of the Act. In terms of content, the Act does not set any substantive requirements for the programmatic approach programme: in principle, any subject relating to the physical living environment may therefore be the subject of such a programme. Article 3.17 of the Act does set a number of requirements for the programmatic approach programme.

We expect that a programmatic approach programme to be particularly useful in cases where:

- precise management of the usable space of use is possible and desirable because an environmental value or other objective for the physical living environment is not being met or is at risk of not being met;

- the environmental value or other objective interferes with socially desirable activities; and

- a case can be made that meeting that environmental value or achieving that other objective and realizing the socially desirable activities is possible by bringing them together in a programme.

Adoption of a programme

A programme may be adopted by the municipal executive, the general management of the water board, the provincial executive and the relevant minister (Article 3.4 of the Act). It is also possible for administrative bodies to jointly draw up a programme, both within the same administrative tier and from different administrative tiers (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 118). The programme then applies to all those administrative bodies.

If the policy in a programme is related to that of other governing bodies, the administrative body is responsible for proper coordination (Article 2.2 of the Act).

Participation is essential in the creation of programmes (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 219). The administrative body must therefore state in the adoption decision of the programme in what manner timely public participation has taken place by explaining how citizens, companies, civil organisations and administrative bodies have been involved in the preparation and what the results of that involvement are (Article 10.8(1) of the Act). If the programme is adopted by the municipal executive, the general management of the water board or the provincial executive, it must also describe how the decentralised participation policy has been implemented (Article 10.8(2) of the Act).

The adopting administrative bodies must arrange for public participation and preparation in accordance with Article 3.4 of the General Administrative Law Act (Article 16.27 of the Act). Anyone may submit opinions, not only interested parties (Article 16.23 of the Act).

The creation of the programme may require an environmental impact assessment under Article 16.4.1 of the Act. The programme also contains an implementation section.

Legal protection

The programme binds only the adopting administrative body in the exercise of its powers. Given this self-binding nature, no appeal to the administrative court is available, in principle, against the decision to adopt the programme (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, pp. 115 and 298).

If any part of a programme provides a direct ground for activities and the programme therefore entails specific legal consequences, that part of the programme may be appealed. The legislature opted for this because these activities are no longer subject to a separate consent decree for the aspect to which the programme relates (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 116).

An example is the management plan for Natura 2000 areas. The parts that relate exclusively to the description of the activities included in the management plan are, however, subject to appeal (Parliamentary Papers II 2013/14, 33962, no. 3, p. 299).

Transitional law

Authorities may adopt a programme even before the Act enters into force. A non-mandatory programme adopted between 23 March 2016 and the entry into force of the Act counts as a programme based on the Act. However, this requires that the programme meets the substantive and procedural requirements that the Act sets for programmes in Article 3.2.1 of the Act (Article 4.11 of the Implementation Act). No transitional law applies to older, non-mandatory programmes.

In addition, the transitional law provides that mandatory programmes under the old law will continue to apply under the Act. Specifically with respect to the mandatory programmes that follow from European regulations (see, for example, Articles 4.56 and 4.57 of the Implementation Act), European law determines the date on which renewal of those programmes is required.

Points of interest for practice

- Review the implementation section of current policies. If these documents contain measures in addition to policy intentions, they may qualify as programmes under the Act.

- Take into account in the preparation of the environment strategy already the environmental values that will be included in the environmental plan. These environmental values may give rise to the obligation to draw up a programme.

- Beware of a programmatic approach programme, because that approach entails making early decisions as to which projects will or will not go ahead. This has major implications.

- It is important that the environmental strategy and programmes remain current and aligned, so that they can continue to function properly.

Final comment

This post is part of the Environment and Planning Act blog series. A list of all the blogs in this blog series can be found here.

Further information on the background and adoption of the Environment and Planning Act can be found on our webpage www.my.stibbe.com/mystibbe/pgo. Our webpage includes the consolidated version of the Environment Act, whereby all the articles of the law are provided with a relevant explanation based on the legislative history.